An awarded alumnus and artist’s approach to overcoming adversity

From the galleries of Austria to the red dirt of Western Australia, Gary Proctor’s artistic career has been a colourful one. Throughout the challenges he’s faced – including the loss of his home and studio in the Black Summer bushfires – his enduring sense of curiosity has kept him moving forward.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this article contains images of deceased persons.

Gary Proctor (GradDipProfArtStud ‘89, MFA ‘94) has always approached life with creativity and curiosity. “All my life, I've made art. When I was a kid, I used to naturally see things in terms of design and watercolours,” he says.

“When I was 21, I built my first house here in Mallacoota without knowing anything about building. You learn on the job, including how innately resourceful you are, and how you can make your own luck.”

Mallacoota, located in Victoria’s East Gippsland region, was battered in the 2019/2020 Black Summer bushfires. On New Year’s Day 2020, Gary received word that his home and art studio had burned down. Lost in the flames, along with tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of art materials, was the UNSW Alumni Award certificate he received in 1996. However, the trophy survived the flames.

Alumni Awards are presented each year to acknowledge the achievements of outstanding UNSW alumni. Gary, who reached out to UNSW for a replacement award following the fire, was recognised for his work in establishing the Warburton Art Project in remote Western Australia.

Considering his many achievements over the years, it’s little wonder we celebrated Gary then, and continue to celebrate him now.

From student to teacher and back again

After growing up in Queensland and the Mornington Peninsula in Victoria, Gary moved to Melbourne in 1988 to study art at the Caulfied Institute of Technology,. Student life didn’t stick, and within a year Gary had left Melbourne to pursue his own projects and eventually work in a full-time art practice.

“It was kind of a studio gallery where people would come in and they'd routinely say ‘I want a copy of Down on his Luck’ or “The Lost Child”. I think I did two of Rembrandt's The Night Watch … you'd paint Alsatians, portraits and anything like that. For two years, I had to do that to pay the rent. It was total painting practice … you had to deliver good results or forget about it.”

Around 1983, Gary moved into a studio where he worked alongside, and became friends with, high-profile Western Australian artists including John Beard, Douglas Chambers and Ben Joel. Through these connections, he was referred for an art lecturing position in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. “I did the interview and suddenly, without any undergraduate qualifications, I got the job,” he says.

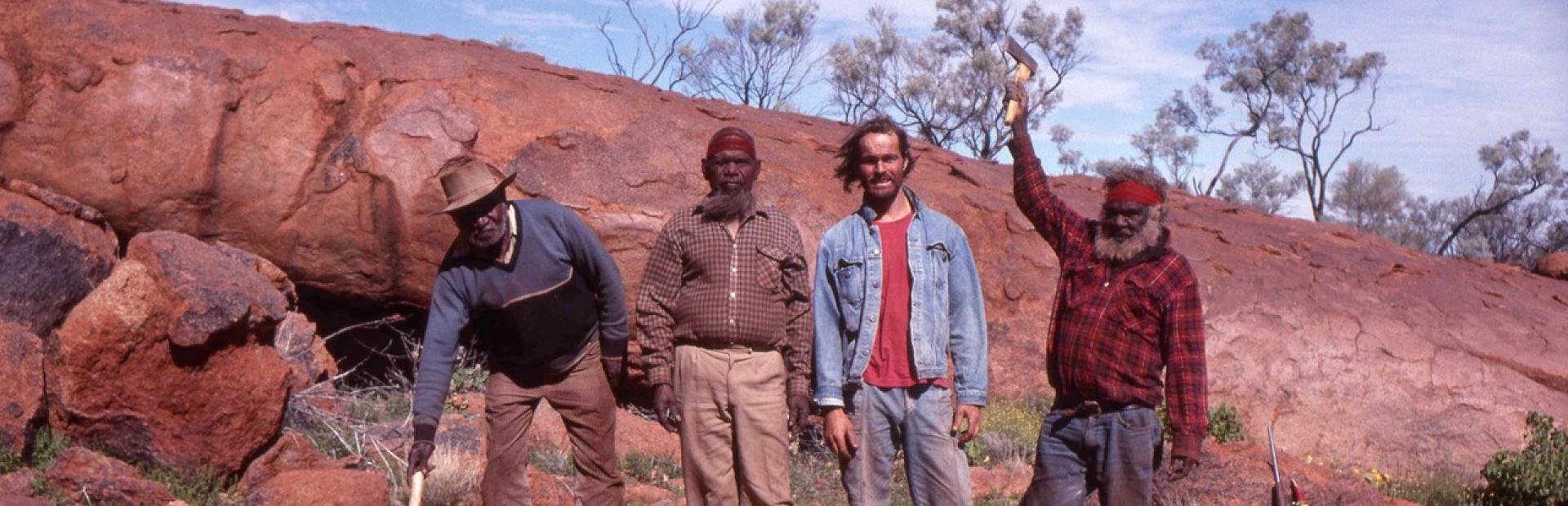

It was during his time teaching in Kalgoorlie and doing outreach work at the Boulder Regional Prison that Gary first began visiting Warburton, located near the Northern Territory border. There, he became involved with the remote Ngaanyatjarra community, a group that would go on to heavily influence his life and artistic practice.

When Gary’s teaching job in Kalgoorlie ended, he found himself at a professional crossroads. He turned down a lecturing role in Perth and returned instead to COFA to begin his Masters degree, which would focus on the Ngaanyatjarra community in Warburton. After a sojourn in Austria, where he did a stint as a guest lecturer, he returned to Warburton to spend a transformative three months living in a remote desert bush camp.

The Warburton Arts Project: a life-changing partnership

Gary’s time in Warburton caused a fundamental shift in his perception of Indigenous cultures, experiences and histories, and began a longstanding relationship with the community in Warburton.

“The whole intellectual and cultural architecture of my knowledge and experience, the things I valued and all of that were called into question at that time. I put them aside and continually tried to leave them there. At the beginning of that time, I had to do a kind of self-cleansing.”

In 1989 he founded and became Director of the Warburton Arts Project, a position he held until February this year and for which he received his UNSW Alumni Award.

|

Back then senior Warburton community members decided to build a collection of cultural material in painting, art-glass, textile and other media to maintain and strengthen Ngaanyatjarra culture, to share this with non-Indigenous people and help build a stronger economic base for community members; Warburton Ranges community is now home to the largest Aboriginal-owned collection of Indigenous art in Australia – a repository of more than 1000 pieces, each recorded with its cultural information and accessible to Ngaanyatjarra Aboriginal people in its comprehensive data base. Renowned internationally, it is of astonishing cultural significance.

“The Warburton collection is a 30-year project with Ngaanyatjarra people of the Western Desert, with their voices being the main ones … a culturally safe and familial environment, where Indigenous people created the meaning of that space.”

|

A new phase of creation

As part of a current Doctor of Arts project, Gary is working to complete the full annotated catalogue of the Warburton collection. He remains closely connected to the community there, but now lives in Mallacoota, where he is re-building his house.

He is pragmatic about his losses in the bushfires, viewing them as ushering in new times replete with new opportunities, similar in some ways to the ones he experienced in Warburton.

“If I could get it all back, I would but I can't, and so it's kind of like that first time when I dropped a lot of the intellectual baggage in that 1989 bush camp … and just left it there and moved on.”

The artist in him is also excited by the prospect of creating something new from the ashes.

“Building another house is just a new experience … The first thing I did, the day after I heard the house had burnt down, was start drawing new plans. I'll build a new house and then it all sort of starts to happen again. Yeah, so it’s kind of where the fun parts start.”